Why we need to take personal responsibility for language use on disability

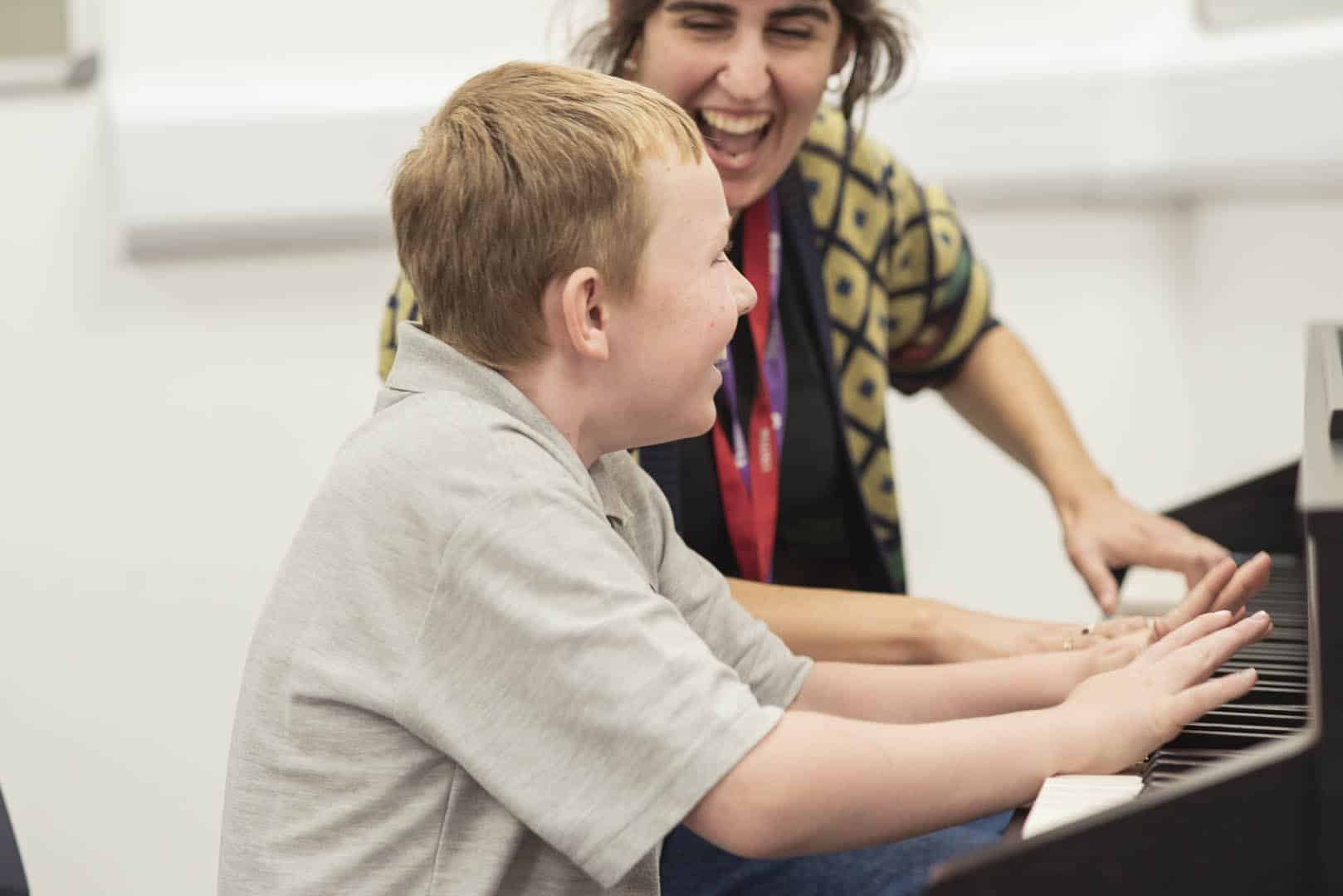

Stella Hadjineophytou, a Nordoff and Robbins music therapist, on why we need to take personal responsibility for the language we use to describe a person’s disability.

Do you ever feel awkward describing a person’s disability? Perhaps you have a disability that people struggle to talk about? How often do you hear “can we still say that these days?” or “is that the right word for it?” Maybe you avoid the topic altogether.

We simply pick the ‘good’ language, right? Respectful phrases, polite words? Well, the problem is that we can’t collectively decide on what’s ‘good’.

As a music therapist, I’ve spent the past year exploring how my profession perceives disability, in addition to how that impacts on our practice with disabled people. While we are often aiming to empower, connect and provide access for disabled individuals in a society that oppresses and marginalises them, music therapists aren’t immune to the influence of structural discrimination.

We must continually challenge our own internalised ableism. A crucial part of this process is examining the language we use to describe disability. Why? Because language is powerful. It represents and shapes our unconscious biases and can perpetuate the very oppression we hope to disrupt.

You might say “Sam is disabled,” or “Sam has a disability,” or even “Sam is living with a disability”. And on each occasion someone could quite reasonably challenge your wording. This is because of a fundamental dilemma: we haven’t yet agreed on a single definition of disability. How can we describe something when we don’t know what it is?

What is disability?

People have been trying to define disability for a while, and their attempts have left us with various definitions, or ‘models’ of disability. We’re going to explore three of the most widely used: the medical model, the social model, and the holistic model.

1. The medical model and person-first language

Closely linked with the healthcare system, the medical model of disability defines disability as an individual deficit which requires remedy through medical intervention. It encourages person-first language, which means referring to people first as individuals before mentioning any disabilities. For example, you might say “a person with a disability” or “Jim is living with cerebral palsy”. Although the intention is to prioritise people’s wellbeing, it could be said that this enforces an unfair ideal of health that frames impairments and differences as a barrier to living a full life. Can you imagine saying “a man with left-handedness” or “Gina is living with artistic skills”?

2. The social model and identity-first language

The social model of disability originates from 20th century activism and defines disability by accessibility. It argues that people who have impairments are not disabled until they encounter systemic oppression. For example, a ramp provides access for everyone, while stairs disable some. It employs identity-first language, aiming to destigmatise disability by referencing impairment as a key part of identity, such as “Fred is Deaf” or “I work with autistic children”. There is a case to be made that this has helped improve both social attitudes and accessibility. Critics argue, however, that the social model is idealistic and overlooks those seeking to change the effects of their impairment on life quality or life expectancy.

3. The holistic model and person-centred language

The more recently developed holistic model of disability rejects a ‘one size fits all’ model. Instead, it employs a case-by-case understanding of disability based on the input of unique lived experience. It encourages person-centred or person-led language, which defers to the language preference of the person or group being described. This helpfully disrupts the infantilising habit of speaking for disabled people, therefore putting them in a greater position of power. But what does that mean for people who are unable to communicate their preferences?

Recognising and challenging

These models influence everything from social attitudes to changes in the law. They have real impact on people’s lives.

Rooted deep in our social structures, their co-existence and overlap have created a complex, contradictory environment which simultaneously embraces and rejects disability.

For example, in 2022 the BBC premiered a TV show with two lead actors with Down’s syndrome but just months before, disabled activists unsuccessfully appealed legislation which permits the abortion of babies with Down’s syndrome up until birth.

I wondered how I was contributing to this cognitive dissonance in my music therapy work. I believed I was rooted in the holistic and social models, working to support and advocate for disabled people. But was I really?

I decided to examine my session notes and was alarmed to find contradiction in my language. I found I used affirmative language such as “joyful,” “together,” and “playful” to describe individuals with whom I felt connected. But used ableist language such as “change,” “barrier,” and “struggle” to describe those with whom I had difficulty connecting.

This worrying correlation demonstrated to me not only the power of language to represent unconscious bias, but to perpetuate it.

Unlearning and relearning

I began to shift towards language that implied my own responsibility to learn and adapt.

“They are unable to stay focused on one task” became “they thrive most when given many short, concise activities.” And “they are reluctant to engage in music” became “I have not yet found a way to invite them into music,” and so on.

Actively reflecting on my instinctive wording helped me identify when I was feeling influenced by an internalised ableist perception. I started to see changes in my musical interactions, which felt increasingly more natural and mutual. Following this, was a transformation in the way I engaged with disability in every aspect of my life.

This is an ongoing journey of discovery for me, and so I invite you to join me in taking responsibility for your language.

Question the words you hear and use, consider the feelings they raise, and challenge the perceptions you hold. Embrace the discomfort of not knowing and position yourself in a place of learning. Ask yourself, how would you want to be understood?

Stella uses identity-first language due to personal preference.

Learn more

If you want to read more about language, perception and power from Stella, you can read the full academic article in Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy.

The full article is called Becoming “Unknowing” and “Inexpert”: Exploring the Impact of Language on Perception and Power in Music Therapy with Kirsty. It further explores how the language of disability affects music therapists’ perceptions of the people they work with.

Latest posts

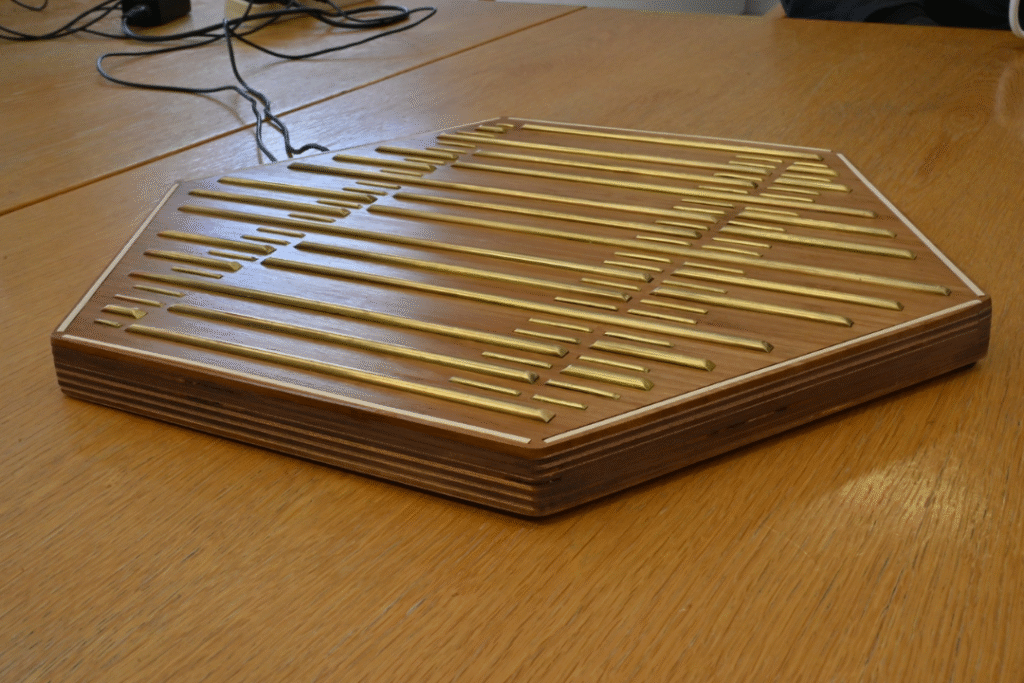

Can technology make music more accessible?

The ‘ReHarp’, a digital instrument designed to support rehabilitation following a stroke or brain injury, is showing how innovation can make music more inclusive, and allow creativity and expression to become a part of recovery.

What is social prescribing, and why is it important?

Social prescribing can take many forms – from the arts, to nature, to physical activity. It can help people in ways that medicine can’t, and the evidence behind music therapy as a method of social prescribing is strong.